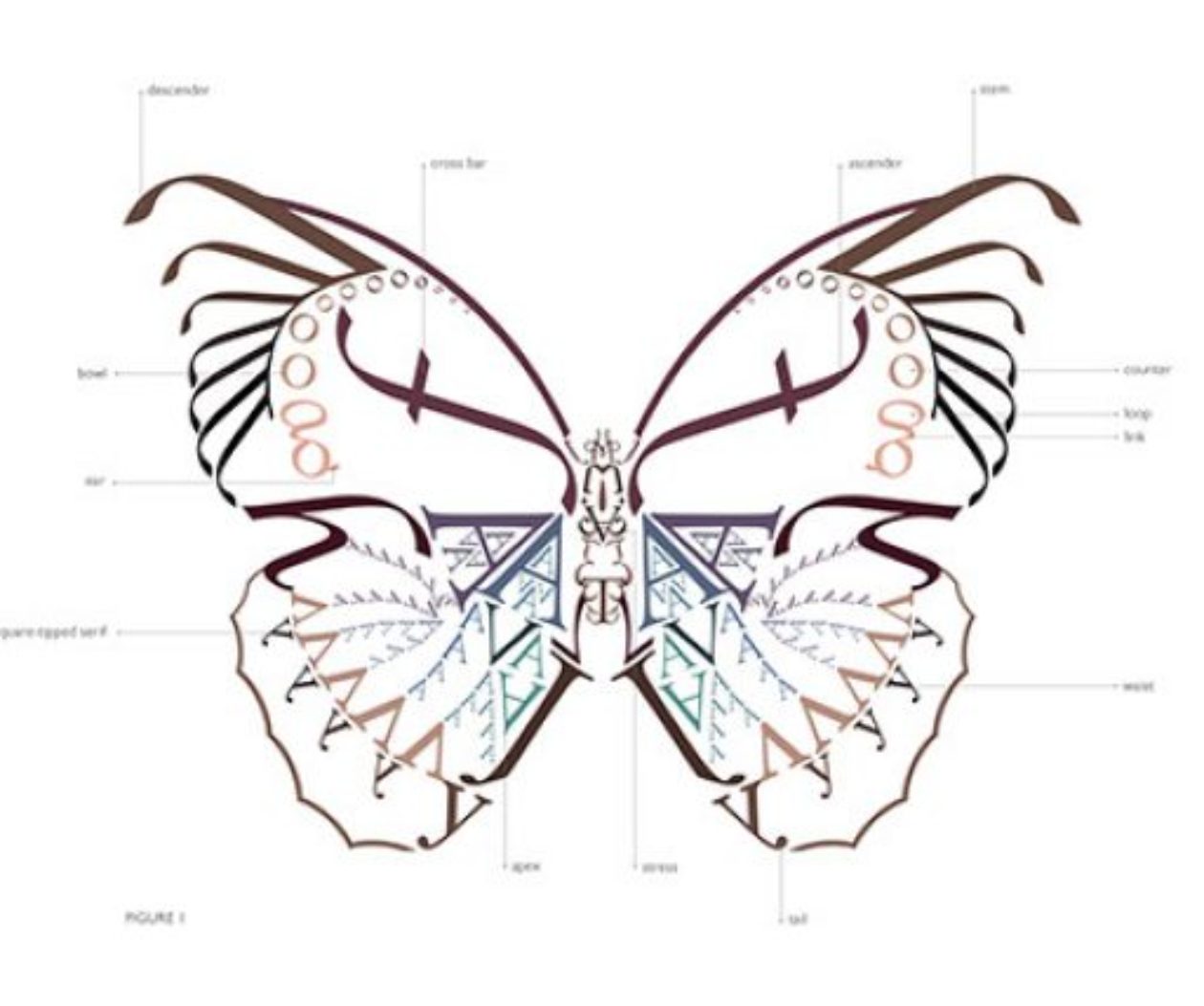

*featured artwork “The 2020s” by Madari Pendas

“You must have sweet blood,” my grandmother told me once when I was a little girl. I supposed she must have been right because every summer my scrawny, freckled arms and legs would be covered in mosquito bites—swollen red mounds like a constellation of stars scattered on my skin.

I would ignore the advice of the adults around me and scratch them incessantly until they would turn into scabs. And without fail, I would pick at them. “You’re going to have scars that will never go away,” my older sisters warned me over and over but the pull to pick was too great.

It was not an itch the picking satisfied but a release I didn’t understand but couldn’t resist. There was something inside me that felt wrong and for that split second when I tucked my nail under the dried brown patch, felt a sharp prick of pain, and watched the ruby red bloom out, some of that wrongness was released.

###

I was 11 the first time I smoked a cigarette. Sitting cross legged on the floor, I held it the way I’d seen women in the movies do. I wanted to be one of them, outside of the little life I was living. No longer the daughter of a deadbeat father. No longer shy and insecure. No longer the girl who was “too emotional.” No longer the one in the class with the learning disability that couldn’t keep up.

I didn’t inhale the first few puffs because I didn’t know I was supposed to. “You’re doing it wrong,” my friend sitting beside me, who knew more about these kinds of things, said. “You have to take it in like a breath.”

I was embarrassed by my ignorance but determined to get it right. I brought the cigarette to my mouth and sucked, swallowing the smoke down. It came out in uncontrollable coughs and my head felt suddenly disconnected, like it was floating in another space above my body.

“Whoa,” I said, laughing.

“You’re having a head rush,” my friend explained.

I didn’t care so much what it was called but I did care that with each inhale, I began to feel like someone else. Not a movie star I had imagined but another thing that felt somehow right. I thought about the dirty smoke coating the pink inside me. I didn’t know who I was supposed to be but I did know I wasn’t supposed to be a girl with pink inside. Now, I could make my body what my mind already believed it should be—tarnished.

And in the years that followed, I would do it again with other things. Things that always felt simultaneously wrong but somehow right.

###

When I was 19, I lived with a boyfriend who abused me. The first time it happened, he gripped my wrists so tight, it left bruises that encircled them like two bracelets. After, I sat in a bathtub and lathered soap on each one with the vague notion that maybe I could wash what happened away. But, over and over, as I dipped my soapy arms into the water, a cloud would burst from each and reveal the deep purple truth.

The last time he hurt me, we were parked in a car on the side of a mountain road arguing about which direction to go in. I remember the map in my hand. I remember the familiar flash of anger that passed over his face. I remember saying, “I’m sorry. Please don’t!” I remember his fist hitting me. I remember putting my hand up to shield myself before the next one. I remember him grabbing that hand and bringing it to his mouth. I remember knowing his teeth had broken the skin. I remember the contrast of the blood seeping out from the fresh lesions on my knuckles—bright crimson against the white of my skin. I remember in that moment that, for the first time, I was tired of being tarnished; I wanted to be pink inside again. And I remember knowing that I was going to leave him soon and never return.

###

Six months later, I sat next to the man who, in seven more years, would become my husband and told him the story of what had happened on the side of the mountain road.

“And you didn’t tell anyone?” he asked.

“No,” I said, the shame washing over me. The feeling that I had done something wrong. That maybe even if I didn’t want to be tarnished anymore, it was too late and I could never really change.

“Why didn’t you tell me sooner?” I shook my head; I didn’t have an answer. “It’s okay,” he said. “I’m glad you told me now.”

Then he took my hand in his and I watched his eyes go to the small scars on my knuckles—the ones no one knew about but me until then. He ran his fingers gently over them, brought them to his lips, and kissed them. And as he did, I knew it was the beginning of something new. From then on, when I saw the scars, I would remember this moment and not how they got there to begin with.

###

I was in my 30s when I started running. I liked the solitude, the way the streets were empty in the early morning, waiting for the day to begin. The air so frigid it stung with each breath or so hot my clothes would turn damp with sweat. I liked the way my muscles burned. The way my mind would clear, forget about the past or the future, and just be there in that moment for a little while.

Some days, I could still feel that wrongness brewing inside me but I had different names for it by then. Anxiety. Depression. Trauma. And on those days, it felt like each time my feet hit the pavement, a little of that wrongness went with it and some kind of new strength began to grow.

And in the years that followed, I would continue doing things that made my body feel stronger and the more I did, the better I felt.

###

When I was 46, I found a cancerous lump in my breast. I asked the doctor, “But how did it get there? What did I do wrong?”

He said, “You may have done nothing wrong. Sometimes these things just happen.”

After surgery and treatments, scans showed the cancer was gone but the same questions cycled through my thoughts again and again. Where did the cancer come from? What had caused it to grow? What would stop it from coming back? Why did my body betray me? I had been treating it right for so many years now.

I grew angry at my body.

One day, I woke up from a restless sleep to find my arms covered in scratches, the sheets stained in blood. It looked as if I’d spent the night wrestling a rabid cat. But I knew there was no cat. I knew I had done this to myself unconsciously as I slept.

Every day after that one, more scratches appeared.

When I showered, I would look at my arms and think about the little girl with the mosquito bites on her skin. More than 40 years later, the constellation had returned but this time it was chaotic mess of lines, some red and some an opaque white. I could hear my sisters saying, “You’re going to have scars that will never go away.”

###

At 47, I sat looking at a therapist. “I’m not doing very well,” I told her and she nodded, then silently waited the way they always do. I thought to tell her about the cancer because that seemed to be what started all this again.

Instead, I began to tell her about the little girl. Week after week, I walked my way through the years—the girl, the young woman, the middle-aged me—and as I did the scratches began to heal and new ones stopped appearing.

I thought about that wrongness I had believed was inside me. When I was little, it felt like a monster, trying to fight its way out. But now I knew there was never any monster; there was always just a little girl with pink inside trying to hold in all the feelings that she didn’t know how to.

“I’’ll take care of you,” I told her. “I’m sorry I haven’t always done that before but I know how to now.”

###

I’m 50 and my body has scars that will never go away. There are the ones on the inside that no one can see. There are the ones on my knuckles, so faint now they can only be found if you know where to look. There is the one on the side of my breast, a perfect symmetrical slice. There are ones on my arms, translucent lines like ghosts whispering secrets from the past. Each one tells a story. I used to think they were the stories of what made me weak. But the more I listen, the more I understand they are the marks of the times I needed to be the bravest. They show when I had to struggle through something, when I had to walk away, when I had to fight, and when I had to heal. They are my body and they are me.

I really loved your essay. The simple truths in you concluding paragraph was great.

Wonderful essay. I loved the structure of it and its universality. It resonated with me.

Thank you!